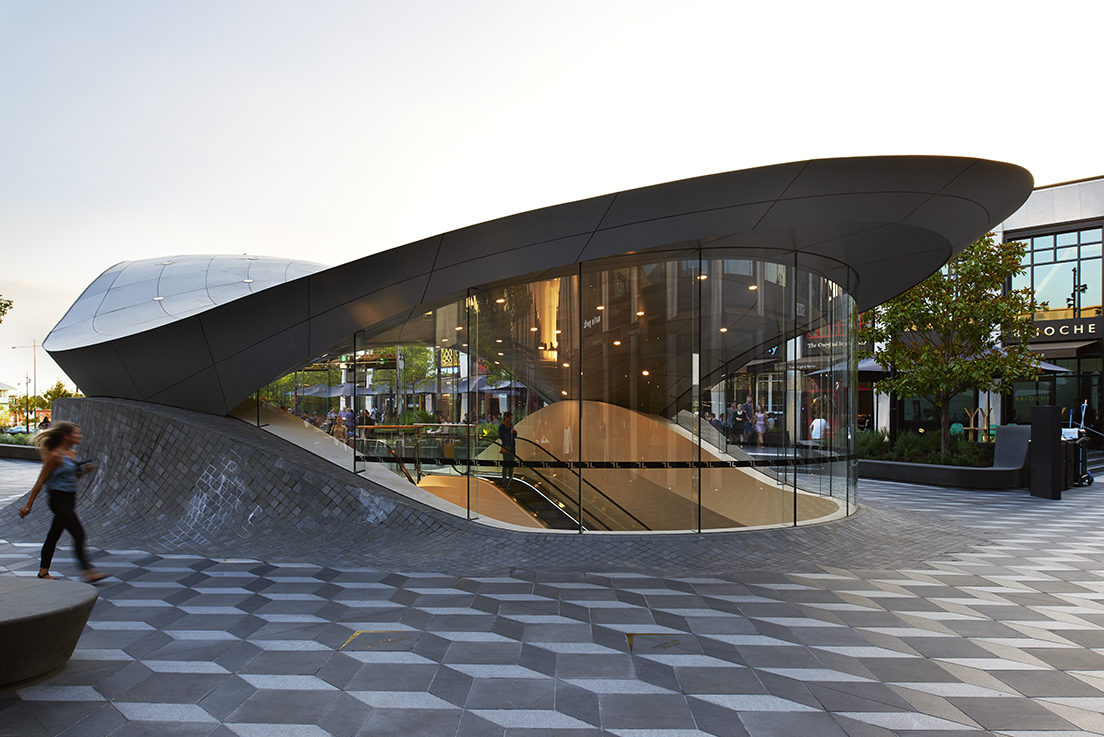

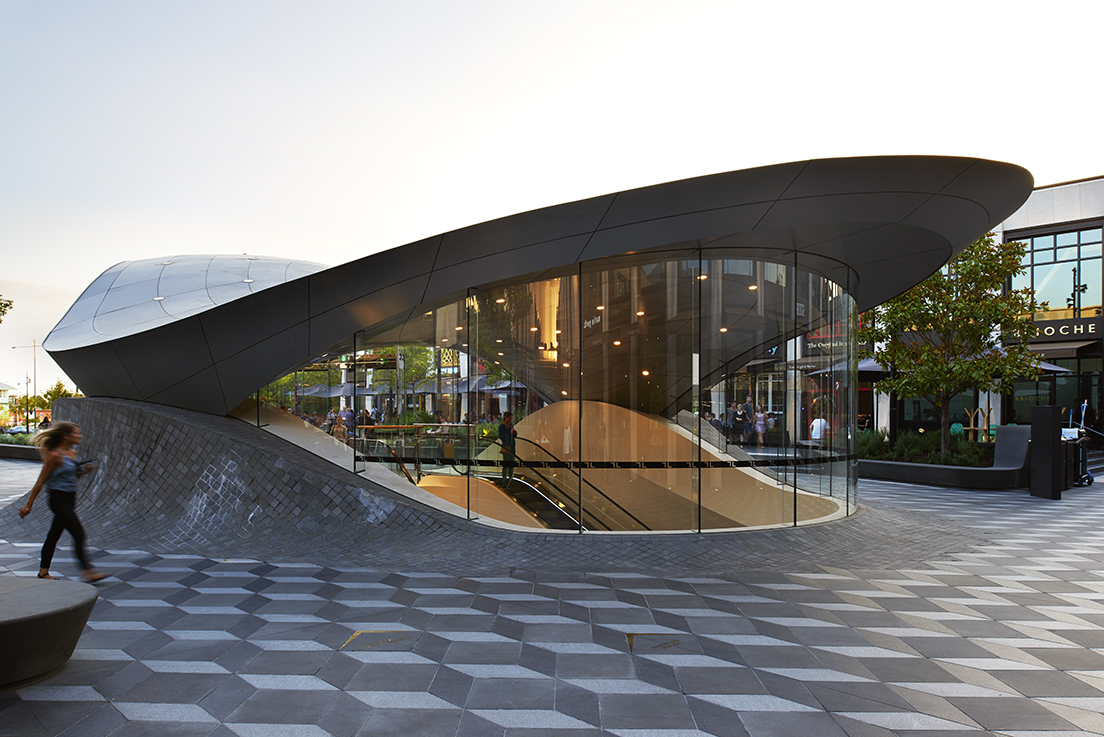

Bringing your vision to life

Creation unfolds in two stages: first in the mind, then in reality. AGC stands as your reliable industry partner, ensuring your project’s journey from concept to completion.

From state-of-the-art airports, to advanced hospitals, and luxurious casinos to lavish homes and impressive corporate headquarters, we consistently push boundaries, redefining the realm of possibilities.

Partners you can rely on

Our collaborative efforts extend to partnering with premier architectural firms, esteemed consultants, and highly skilled engineers, in addition to forging alliances with top-tier construction companies.

Whether it’s harnessing the power of advanced technologies, navigating complex challenges, or achieving remarkable results, our partnership is a gateway to success.

Tailored solutions for every grand idea

Embarking on grand ideas requires bespoke solutions, and with our worldwide partnerships, we ensure no vision goes unrealised. Each project is met with a tailored approach, leveraging our global network to craft solutions that surpass expectations.

Proven process. Assured outcomes.

Our processes have evolved through years of collaboration and attentive listening to our clients, leading us to adapt and tailor our approach accordingly.

Whether it’s extensive commercial developments or custom home designs, our assured outcomes stem from meticulous quality management and enduring relationships with partners, ensuring the realisation of our clients’ desired results.

Conceptualise

Every project begins with a conversation. Let’s discuss your vision.

Propose

We’ll align your requirements with leading industry solutions and customise options to suit your needs.

Deliver

Let us seamlessly manage your project, overseeing procurement, manufacturing and delivery.